"I am not African because I was born in Africa, but because Africa was born in me" Kwame Nkrumah

As a white American who descends from European immigrants, that quote is awkward to say. It makes me feel like a square peg in a round hole - something that doesn't quite fit. My lineage traces primarily to Italy and Ireland, with smidgeons of other northern European ethnicities mixed in. I am a classic mutt, but entirely from within the confines of Europe, or so I assume. Looking at me, you would have little doubt about that assertion. Surely, I am not born in Africa or connected to the continent.

Yet upon further reflection, the square pegs’ edges round. I am indeed born in Africa. Africa is born in me. We are all of Africa.

Africa birthed us. Our species, Homo sapiens, evolved and was born in the forests and plains of Africa. From there intrepid souls migrated and spread out to all corners of the globe. This heralds Africa as the birthplace of humanity. That initial human population was small, a genetic bottleneck that leads to a noteworthy and startling fact. Genetically speaking, we are practically the same, much more so than other species. This makes Homo sapiens a unique limb on the tree of life. As brothers and sisters each of us is more closely related to each other than individual members of other species are related to each other.

Humans share with each other 99.9% of DNA, the material of our genes. The genetic alphabet soup of A, T, G, and C that write our collective genetic story is nearly the same in all of us. There are a few differently spelled words in this DNA language. This contributes to the beautiful expression of diversity within humanity. It is only that .1% of difference that results in all of the multitudes of variations of traits and characteristics that contribute to that beauty.

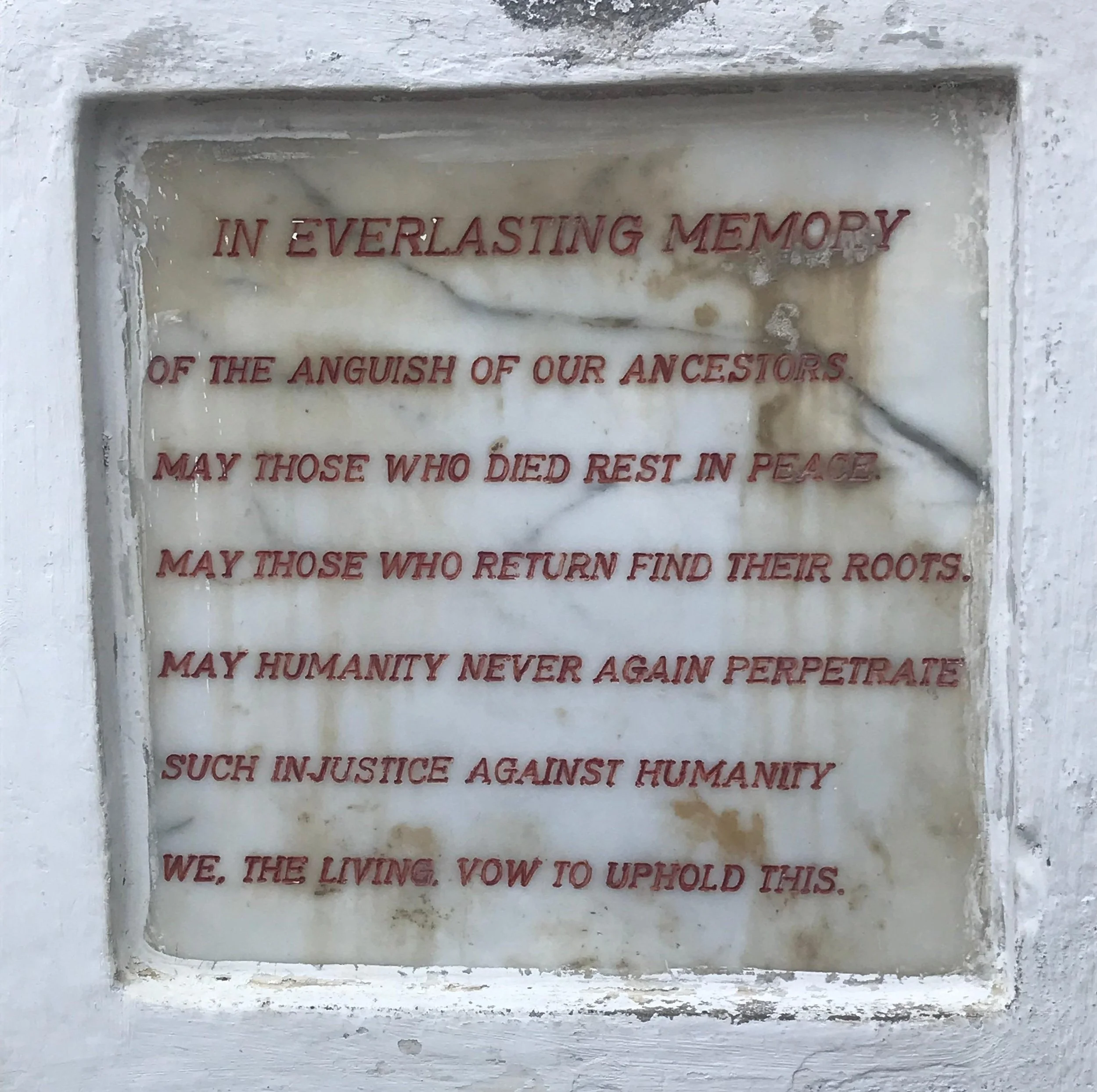

That minute difference has also caused harm and injustice. It is because of biased interpretations and power dynamics that the mere .1% difference is distorted as the twisted rationale to the constructs of systemic racism, inequality, and injustice that can result in crimes against humanity. But the fact remains, genetically speaking, we are as close to clones as we can get. And the birthplace of that combination of genes was here, on the African continent. All of humanity descended from Africa.

The Ga people, whose traditional lands consist of the coastal strip that encompasses Ghana's capital, Accra, acknowledge this. They welcome us. Specifically, they welcome us home. They invite us to connect with humanity. They invite us to connect with our ancestors. They invite us to re-connect to our birthplace. In the Welcoming Ceremony the Ga Elders ask for your Ghanaian day name that is based on the day of the week you were born, and ask to cite those ancestors you brought with you. Because I was born on a Saturday, my name is Kwame. The ancestors brought with me are Jack and Rita, Alfred and Theresa, John and Ina. The ritual proceeds by consecrating the land with alcohol, imbibing spirits, and connecting to land physically, emotionally, and spiritually. Welcome home! Akwaaba! Wherever you have been, you are welcomed, though that Twi welcome is distinct from the Ga term.

Coming home to Africa is a spiritual transformation. African spirituality is not just ancestral and a thing of the past, but is a living and breathing entity within each one of us. It is holistic and purposeful. Ignoring the distractions and fragmentations of contemporary life to come home uncovers a wealth of connections and spirituality that our consumer oriented society prefers you to forget.

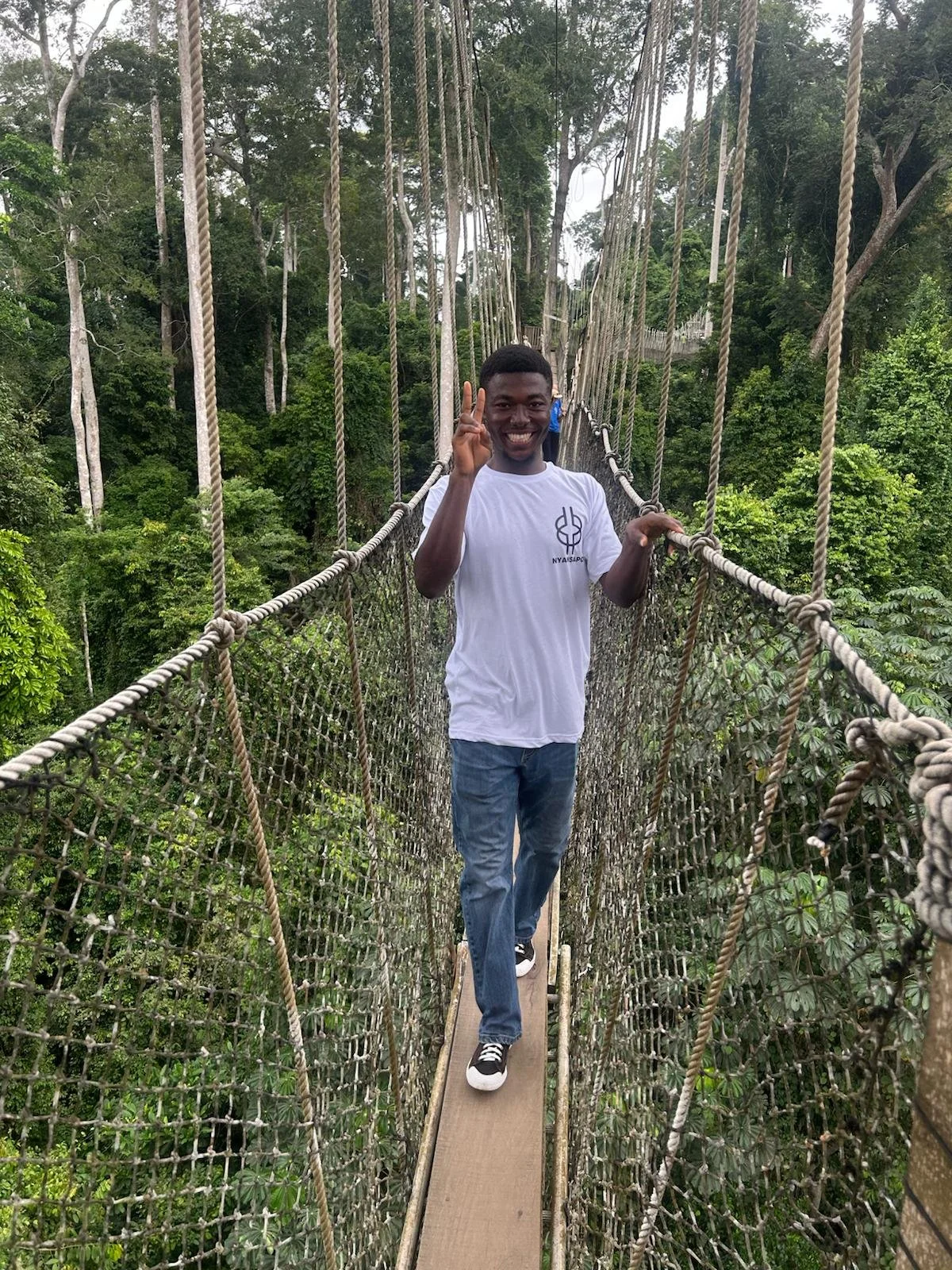

Professor Pashington Obeng reminds us of this during our visit to Aburi and Ananse Kwai, a preserve of medicinal herbs and purposeful plants. African spirituality is a way of life that requires us to earn our 'personhood' to fully become an ancestor one day. Achieving such requires living a moral life to become a better person that connects to the community, the land, and the ancestors. Within this ethic is a cycle of living and learning where the beginning is the end and the end is the beginning. This runs counter to the hyper-individualistic linear worldview that slices and dices the community with the intention to benefit the few.

In African spirituality, birth and death are not the beginning or the end, but part of the ancient cycle of living and learning. This dynamic is represented by the Adinkra pictograph, Sankofa - learning from the past to move forward into the future. And it is in this sacred land, where humanity's birth is commemorated, and our human essence revealed. Sankofa is within. The cycle continues.

The Witness Tree Institute of Ghana brings us home to that birthplace. It is here in Ghana where we invite the stranger within to reconnect, and to shed preconceived notions of what it means to be human. It is here in Ghana where we experience the essence of humanity. It is here where we can state with assuredness, that Africa is born in us.

David Duane

Chair of Science Department, Fenn School and Board Member of The Witness Tree Institute of Ghana